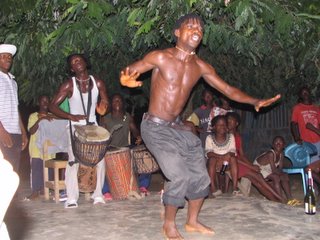

drummin' and dancin'

My camera ran out of batteries at the beginning of the night. It was probably for the best because the photos couldn't have possibly captured the spirit of the evening and would have only been a disappointment. It was my friend Emma's birthday and we surprised her by hiring a Liberian drum and dance group to play that evening outside our guest house. Around 60 people, coworkers, friends and neighbors of all ages and colors gathered for a candlelit performance.

The group agreed to pay for about $25 and a bottle of gin, and it was clear that they had had at the bottle before the "gig"- but remarkably whatever they had been drinking or smoking only added to their passion and skill. I don't know quite how to explain it, except to say, I've seen fair amount of dance in my day, but my jaw was on the floor and eyes blinking in disbelief a good part of the time. Before I came to Ghana I saw a documentary called Rize (see it!!) about an underground hip-hop dance movement called "crunking" or "clowing" that is a kind of spasmodic cathartic dance style where dancers' limbs move with such speed that the director actually felt it necessary to add a disclaimer to the start stating "no film has been sped up in the making of this movie." Well, the dancing started off in this vein - legs and arms moving at impossible velocities and in perfect sync with the captivating polyrhythms of the drums. This would have been impressive enough (jaw already on floor), but then the dancers moved into these acrobatics and contortions that would have easily impressed a cirque de soliel recruiter.

OK. So, I'm already impressed. But wait... After each dancers had finished dazzling us, they would casually walk back to the drum line and relieve another drummer - picking up his instrument without skipping a beat and assuming the role of musician. I thought, what are the odds that such incredibly talented, strong and dexterous dancers could also be such gifted musicians? Literally, the lead drummer (who I assumed was kept out of the dance portion because he talents were really more rhythmic) got up at the end did higher flips and more painful-looking contortions than all those who preceded him.

Not only was this one of the best music and dance performances I’ve ever seen at any venue, but we had the added bonus of being a mere 5 feet from the dancers and drummers and of even being dragged on the dance floor one at a time, much to the amusement of our Liberian friends. At other points it broke out into an all ages dance party. In fact about the best dancer was all of 3 years old. There such a lack of self-consciousness and a playful sensuality about the way people dance here that is just infectious. And anyway, it would be hard not to move your body to the rhythms – sometimes you don’t even notice that a part of your body has begun to dance despite yourself. The only shame of it was that these guys are stuck on a refugee camp playing for $25 and a bottle of whisky. They have big dreams though recently won a competition in Accra. I know they would be a huge success if they could get booked at any festivals in the U.S. If anyone can help in this regard, please let me know!